How often do you read something that forces you to confront your existence in the social world?

I had the opportunity to engage in the Illuminate Universe x MeaningfulWork: The Power of Social Innovation work-integrated learning experience through their Community Leadership Program and I am delighted to share some of my formed thoughts and reviews after sitting with the material. While I already have background knowledge and experience in the arenas of sociology, philanthropy, and design thinking, this learning and leadership experience gave me a concise schema of social innovation to help navigate the complexities of both social problems themselves and the tenuous processes involved with developing and implementing solutions aimed to manage or address them.

What is Social Innovation Anyways?

It is best to start with the broad definition of the concept used in the learning experience as the process of creating and practicing new ideas to address social or environmental concerns.

This is best understood by applying the constitutive lens–which provides the framework for this article–to the social world, which implies that for- and non-profit organizations are not mutually exclusive, but interdependent. A quote from the learning experience illustrates the relationality of the two sectors quite nicely by pointing out the common element that binds them together:

“Within the first 2 years, 20% of new firms fail. According to a 2014 Nielsen research, successful people focus on ‘walking in the customer’s shoes to unearth critical demand-driven insights.’”

In other words, successful people focus on empathizing with their target group (customers, clients, audience, etc.). This also entails storytelling–you tell yourself a story when imagining your target group’s life experiences, then you tell that same audience the story behind the solution or strategy you develop for them. These are the main messages that Illuminate is aiming to get across by partnering with a contemporary non-profit like MeaningfulWork, encouraging learners to: Be aware of pain points globally, across diverse groups of people; research a niche so thoroughly and conscientiously that there is always an idea on deck; and iterate social innovations until they become effective and inventive enough to achieve the intended goal.

Putting Theory Into Practice

Now that we understand the concept of social innovation, we can take a look at the practical model Chatterjee sets out in the learning experience to help guide the process of creation:

Personal purpose: The Hedgehog Model can be useful here, as it asks what your deepest passion, greatest strength, and economic engine is in order to determine the story and purpose which lie in the intersection of all three (Collins, from Berlin’s “The Hedgehog and the Fox” (1953).

(Source: Jim Collins)

2. Problem identification: Concentrate on addressing the main cause of a problem instead of solely treating the symptoms. One way to do this is using root cause analysis (RAC), where you (1) define the problem, (2) ask why is it happening, then (3) ask why is that? four times (Toyota 1930s). Here is a basic example:

(Source: Business Map)

3. Developing solutions: This entails design thinking, a cyclical process of: empathizing (with the target group), defining, iterating, prototyping & testing.

(Source: Neilsen Norman Group)

This may all sound exciting and perhaps complicated too, and I promise it is always best to read directly from the source material itself. But my simplest takeaway here is the idea that focusing on achieving one quality goal by putting a lot of thought and reflection into its planning and development–even when this is repetitive and tedious–is better than pursuing a variety of goals without dedicating enough time to them individually–even when this seems more expedient.

Reflections

I was able to apply some of these ideas when I started to reflect and evaluate my knowledge of and contributions to the abundance of interconnected environmental problems and their nuanced social “symptoms” (i.e. consequences) in our society which are presented in the work-integrated learning experience.

Specifically, one of the learning videos listed the world’s most pressing issues; namely, the ever-present environmental dangers of global warming, pollution, their related effects (e.g. acid rain, deforestation, low biodiversity, etc.), as well as overpopulation, waste disposal, and diminished public health. All these issues, while weighty on their own, are interconnected–just like the corporate and non–corporate worlds–and these compounded threats can have serious implications for societal health and safety.

On a personal level, this made me think about how even my everyday patterns of behaviour as an urban dweller are part of larger social structures: Whether it is my consumer spending habits, energy consumption, or the methods of transportation I use to get to work and school, even the seemingly inconsequential choices I make come with a set of social repercussions that affect others–even when I cannot see the direct impacts myself. And rather than trying to tackle these problems using individual, small-scale solutions, the work-integrated learning experience reminds me that it is best to focus on a broader goal with coordinated outcomes that will have trickle down effects. Indeed, any of my attempts to modify the above three behaviours (among others) should be understood as part of a larger strategic process of unlearning overarching societal patterns of overconsumption, which includes not just the actions themselves but the meanings and beliefs we associate to them.

On a broader scale, however, these interconnections call to mind the acutely stressful mass humanitarian crises taking place simultaneously around the world. The collapse of social safety networks (ex. hospitals, schools, workplaces, embassies, etc.) often due to geo-poltical challenges difficulties (ex. extreme heat, limited access to clean water, overcrowding, etc.) among other factors exemplify the recursive relationship between the environmental and the social.

“People flee floods in Karachi, Pakistan, August 2020.” (Source: Keystone / EPA / Rehan Khan)

These large-scale wicked problems also tend to have a taken-for-grantedness by virtue of their extreme intricacy and the subsequent difficulty of defining and solving them, but also because they disproportionately impact those marginalized groups in society whose collective lack of privilege is often oversimplified into individual, moralistic terms in order to justify and preserve cultural hegemony.

This is why it is so important to contextualize the idea of doing narrow, rigorous, and ongoing research on a problem–so that the ideas produced for it are specific and effective enough to manage and/or solve it–across the backdrop of intersecting lines of influence, power, and oppression that link the problem and/or condition to all of our other world issues.

The Big Picture and Practical Directions

Many scholars have investigated the intersections between our social-cultural, environmental, and economic worlds; and as many have aimed to categorize peoples’ behaviours inside of them, especially in the biological, psychological, and social studies.

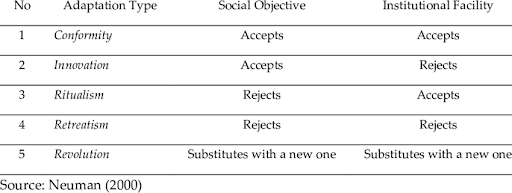

Of particular interest here is American sociologist Robert Merton’s (1938) famous theory of “Social Structure and Anomie,” where he focuses on how differential opportunity structure and rigid social hierarchy create a vast disjuncture between common Western cultural goals of success (material wealth, prestige, power, etc.) and the legitimate means of achieving them (Merton, 1938). This exertion of definite pressure on certain people in society surfaces feelings of frustration and even cultural chaos i.e. anomie, leading people to modify their behaviour to manage it (Merton, 1938). This is where Merton’s schema of five modes of adaptation comes in: (1) conformity; (2) innovation; (3) ritualism; (4) retreatism; and (5) rebellion (1938).

(Source: Neuman / Research Gate)

Each adaptation puts specific emphasis on goals and means, but Merton was particularly interested in the illegitimacy adjustment–innovation–where legitimate means are scrapped for technically expedient ways to achieve cultural goals (1938). This is where our social innovators like Chatterjee and other entrepreneurs and activists fall, and Merton’s theory specifically illustrates how this type of behaviour (and work) is actually a normal response to the pressures and disjunctures of highly complex societies.

(Source: European Social Fund Plus)

What this means is that I have started to see myself as part of this category of people, an innovator, even though I have not accomplished any sweeping social changes. I recognize that I embody the traits of an innovator as a naturally empathetic storyteller, with most of my extracurricular and work experiences revolving around interpersonal communication, but also creating initiatives aimed to address a specific problem.

My participation in RBC’s Design Thinking Program (DTP) at my university exemplifies my leadership journey and style: While my STEM teammates were best equipped to handle technical features of our financial management app prototype, like our AI (Artificial Intelligence) chatbot, my strengths rested in developing the social aspects of our design. For instance, when our team decided to add a trivia feature, I researched and developed questions that address common themes for our target audience of international students, the pain points of which I also chose to elucidate in our final pitch presentation.

Where my work lies as a community leader, then, is continuing to stay engaged in the cycle of theory and practice within the world of social innovation by applying my current skills (empathy, storytelling, interpersonal communication, etc.) to new projects, whether that is by joining an organization dedicated to causes I am interested in; participating in another design thinking-type of program; or embarking on a personal research project.

So, What Should I Do?

This all leads me to my final point of reflection: Tips and advice I have for readers and leaders like me with the kinds of aspirations described in the learning and leadership experience.

Conduct thorough research.

(Source: Alpha Kappi Psi)

In our digital age, there are many diverse research materials which can be found at the click of a keyboard– but it is wise to be critical of the ones you use. If you are unfamiliar with the ins and outs of academic research, I would highly recommend consulting with your local library and/or their website for things like advanced searching strategies (ex. using quotation marks for key phrases); guidelines on assessing the content and source quality of research materials, where peer-reviewed journal articles are often taken as the standard; and writing citations in specific styles (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.), often with the help of online resources like Purdue Owl.

2. Learn how to story tell.

(Source: The Big Bang Partnership)

Storytelling has far-reaching historical roots as a valued traditional practice in many cultures, and its value cannot be lost on us even in an industrialized, technocratic world as it is indispensable to help start and maintain the empathetic process of research, definition and problem-solving, since all of this is based on the stories and experiences of a target group. Working on this skill can involve something as simple as reflecting on meaningful, or even everyday experiences of yours by writing or speaking about them and then going over the story you have told; consuming storytelling literature or media, like memoirs or listening to TEDx speakers; or perhaps pursuing its academic study in places like language and/or writing courses. Storytelling also helps us develop bonds with the key stakeholders whom we are consulting with, directing our work towards, or presenting our solutions to by bringing the emotional, human dimensions of professional work to the fore; to rephrase, storytelling helps us network effectively!

3. Build a robust network.

(Source: Northwest Executive Education)

An indispensable way to find inspiration and meaning in professional work is by creating connections with other leaders in one’s field–and this might ring especially true for an industry as dynamic, energetic, and necessary as social innovation. Networking enables you to glean valuable insights from others’ professional experiences; develop rapport with industry leaders; and, ideally, spark meaningful relationships/partnerships that can lead to new ideas and projects. By extension, networking provides you with the opportunity to share your research findings and receive valuable feedback on your ideas. Whether you are already familiar with it or not, a great starting point is the seminal networking platform LinkedIn, which connects professionals using a messaging platform, the ability to interact (like, comment) with others’ posts, and gain exposure and access to professional and creative resources and opportunities, like their job postings. But you can also network directly within the institutions and organizations you are already a part of (school, work, extracurriculars, etc.) or get involved in specific networking conferences and events to upskill.

These three practical tips echo the concise, procedural nature of social innovation and the messaging which surrounds it to bring to light a coherent understanding of the extremely complex–sometimes, seemingly impossible–issues tackled in the industry.

Conclusions

My learning and leadership journey with Illuminate and MeaningfulWork has been profoundly enlightening. It has not only expanded my understanding of social innovation and the importance of persevering with a single, well-defined goal, but also underscored the intricate connections between the social and the environmental by encouraging me to think about global issues and thereby reinforcing the need for strategic, holistic innovation.

As I integrate these insights into my own work and aspirations, I am reminded of the critical value of continuous learning and adaptation. By leveraging skills such as rigorous research, interpersonal storytelling, and meaningful networking to build robust professional networks, we can enhance our capacity to drive social change.

Ultimately, this experience has reaffirmed my existing commitment to developing and implementing impactful initiatives by providing me with the tools and knowledge needed to navigate the complexity of social innovation, and to approach the challenges I face with purpose and perseverance.

Citations

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social Structure and Anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672–682. https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686.

Comments